This post was originally published on this site.

It was a crisp September afternoon in London. Thanks to COVID, my wife and I were enjoying a long-overdue holiday celebrating our 35th wedding anniversary. We took a leisurely stroll through Kensington Gardens on a glorious Saturday replete with countless families out playing in the sun. We made our way south until we hit Kensington Road and took a left. I recognized the Iranian embassy building immediately. This was ground zero for Operation Nimrod.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Operation Nimrod – The Genesis of Modern Counter Terrorism Operations

Police officers from the London Metropolitan Police (Met) had erected temporary barricades to complement a robust security fence. There was a protest taking place across the street. Angry Muslim women were shouting about the death of Mahsa Amini in police custody. Amini was arrested by the Iranian Morality Police in Tehran for violating their draconian hijab laws and was subsequently murdered. As I typed these words, there was violence breaking out across that chaotic country. Godspeed to the protestors.

The Iranian flag flies outside 16 Princes Gate, and, aside from the shouting across the street, all was peaceful. However, 45 years ago, that was most definitely not the case. That was the day the entire world changed just a little bit.

That’s not hyperbole. If you have ever hung a light on your weapon or saw a tactical team in action, all that started here. It was the SAS assault on the Iranian embassy in London in 1980 that drove the world’s military and LE agencies to get serious about the counterterror business.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The History

May 5, 1980, was a Monday. Six days prior, half a dozen armed Iranian terrorists representing the Democratic Revolutionary Front for the Liberation of Arabistan (DRFLA) had stormed the Iranian embassy at 16 Princes Gate, seizing 26 hostages. Led by one Oan Ali Mohammed, the group demanded free passage from Britain for themselves as well as the release of 91 political prisoners held in Khuzestan.

In the immediate aftermath of the removal of the Shah by forces loyal to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1979, certain Arab minorities in Iran found themselves mercilessly persecuted. Helpless to find redress and enjoying overt support from Iraq, Oan Ali Mohammed and his men hoped to pressure the theocratic government in Tehran to bend to their will. However, Margaret Thatcher, rightfully known as “The Iron Lady,” was having none of that.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Among the hostages was a Met Police Constable named Trevor Lock, who was armed with a concealed revolver that the terrorists failed to discover. Lock was a stabilizing influence upon the terrorists amidst the stress of the siege. His restraint with his firearm until the final attack undoubtedly saved lives.

Lead Up to Nimrod

The world in 1980 was a very different place from what it is today. In the decade leading up to the siege, only Israel and the UK maintained a standing federal counterterrorist capability as we might imagine it today. In 1972, a dozen Israeli Olympic athletes were killed in Munich during a botched effort to stop Palestinian terrorists. A week prior to the Iranian embassy takeover in London, the U.S. Army Delta Force had launched its failed effort to free American hostages held in Tehran.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Delta Force, under the guidance of Special Forces Colonel Charlie Beckwith, was itself patterned on the British 22nd Special Air Service Regiment. However, Operation Eagle Claw—the ill-fated hostage rescue mission in Iran—had failed under cover of darkness in an anonymous Iranian desert. By contrast, after six days of fruitless negotiations, the world’s accumulated press was liberally arrayed around 16 Princes Gate. Whatever the ultimate resolution to this crisis, the entire planet had a front-row seat.

Hardline Policy

It was published British policy not to capitulate to terrorists. Met police negotiators strived mightily to resolve the situation peacefully, but the Iron Lady’s military advisors nonetheless frenetically planned for contingencies. Interestingly, the first word that the British Special Forces operators received that trouble was afoot came from a SAS dog handler seconded to the Met who notified his mates to make ready. Shooters from the Regiment’s B Squadron had immediately launched into planning and rehearsals. Now they were staged and ready to go.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

After six days, all involved were getting tired. The terrorists had released a token few hostages, but they grew increasingly frustrated. Abbas Lavasani, the embassy’s Cultural Attaché and a pro-Khomeini zealot, had been antagonizing his captors on subjects both religious and political throughout the ordeal. In a moment of passion, the terrorists shot Lavasani and threw his corpse out the front door. Prime Minister Thatcher subsequently signed over tactical control from the police to the military and authorized Operation Nimrod.

Go, Go, Go!

The SAS had emplaced discreet cameras and microphones to gather intelligence on the embassy building in the interim between the takeover and the murder of Lavasani. They had also quietly emplaced rope anchors on the roof and surreptitiously removed bricks from the wall in the adjoining Ethiopian embassy to facilitate a breach. The target building was five stories tall with 51 separate rooms. The hostages were segregated by gender and heavily guarded. Throughout it all, the world’s major press outlets maintained a 24-hour vigil, their cameras rolling for that coveted Pulitzer-grade image.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

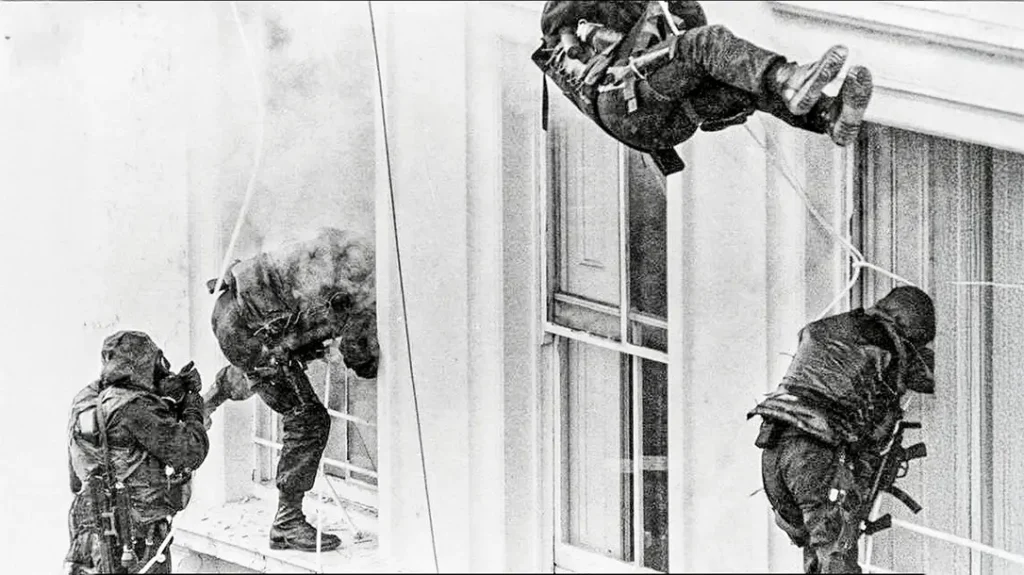

At 19:23 hours on day six, some 35 SAS operators, divided into two teams designated Red and Blue, initiated a simultaneous assault. The two assault teams breached windows, doors, and walls using frame charges and sledge hammers while deploying stun grenades. Troopers rappelled from the roof to enter through upper-story windows in full view of the TV cameras.

Enter the MP5

Rusty Firmin, one of the SAS assaulters, later explained that each operator packed an HK MP5 along with three spare magazines in a thigh carrier. Their Browning Hi-Power pistols each carried an extended 20-round magazine along with another pair of 13-rounders. The operators wore plate-style body armor. Their black fatigues and respirators were designed to give them an intimidating, otherworldly appearance. The respirators and modified NBC hoods also helped combat the effects of smoke and CS gas.

The SAS purportedly lacked sufficient standard MP5s to arm all the assault troops. As a result, a few of the shooters carried stubby MP5K models. Each team had one trooper armed with a suppressed MP5SD as well. Some of the German SMGs were equipped with bulky D-cell Maglite illuminators, bore-sighted to the guns.

A Time to Kill

One of the assaulters, Sgt. Tommy Palmer became entangled in his rappel rope while abseiling down from the roof. He was badly burned when drapes soaked in kerosene by the terrorists were ignited by CS and stun grenades. Fellow team members cut him loose, and he resumed the assault despite his injuries. As a SAS trooper smashed through a window, the terrorist leader Oan Mohammed turned to fire.

Trevor Lock, the police constable held among the hostages, drew his hidden revolver and tackled the terrorist commander. The SAS man disengaged from his ropes, shouted for Constable Lock to get clear, and emptied a full 30-round magazine into the terrorist leader, killing him instantly.

Threw Out Their Weapons

At the sound of gunfire, the two terrorists holding the main group of male hostages on the second floor opened fire, killing Ali Akbar Samadzadeh and wounding two others. When they heard the approaching SAS troops, they purportedly threw their weapons out a window and waved a white flag. The story goes that the first SAS team to enter the room pressed them both against a wall and killed them with bursts from their MP5s.

Two terrorists attempted to blend in with the hostages being escorted out of the building. One was found to have a Soviet RGD-5 fragmentation grenade. A nearby SAS trooper named Pete Winner struck the terrorist in the neck with his German submachine gun, knocking him clear of the escaping hostages. Two other SAS soldiers then cut him down. One of them dropped the live grenade, its pin intact, in his pocket and continued the mission.

Trying to Blend In

One terrorist, Fowzi Badavi Nejad, successfully mingled with the hostages. A SAS operator identified the man in the outside yard and dragged him back into the building with the likely intent of killing him. Realizing they were being observed, the SAS man took him into custody instead. Nejad subsequently spent 27 years in a British prison and was paroled in 2008. As deportation to Iran would have meant certain death, Nejad was allowed to remain in England after the completion of his sentence. He lives in South London under a new identity today.

Aftermath

A subsequent police inquiry ruled the killings justifiable homicide. This operation was later characterized as one of the most seminal events in British history. The tactics, weapons, and gear used during Operation Nimrod ultimately influenced counterterror units around the world.

The Iran-Iraq war began five months later, and the DRFLA was largely forgotten.

The televised operation brought the normally reclusive SAS into the light. Heckler and Koch could not have gotten better exposure had they purchased advertising at the Super Bowl. In short order, every cop in America wanted a set of black fatigues hanging in their closet and an HK MP5 in the trunk of their squad car.

Operation Nimrod

The truly sad thing about the whole sordid mess was that the terrorists were sort of the good guys. The Islamic dictatorship in Tehran has been a thorn in the side of the free world since 1979. It is simply that seizing an embassy and shooting a man in cold blood simply cannot be

The post Operation Nimrod – Counter terrorism Game Changer appeared first on Athlon Outdoors Exclusive Firearm Updates, Reviews & News.