This post was originally published on this site.

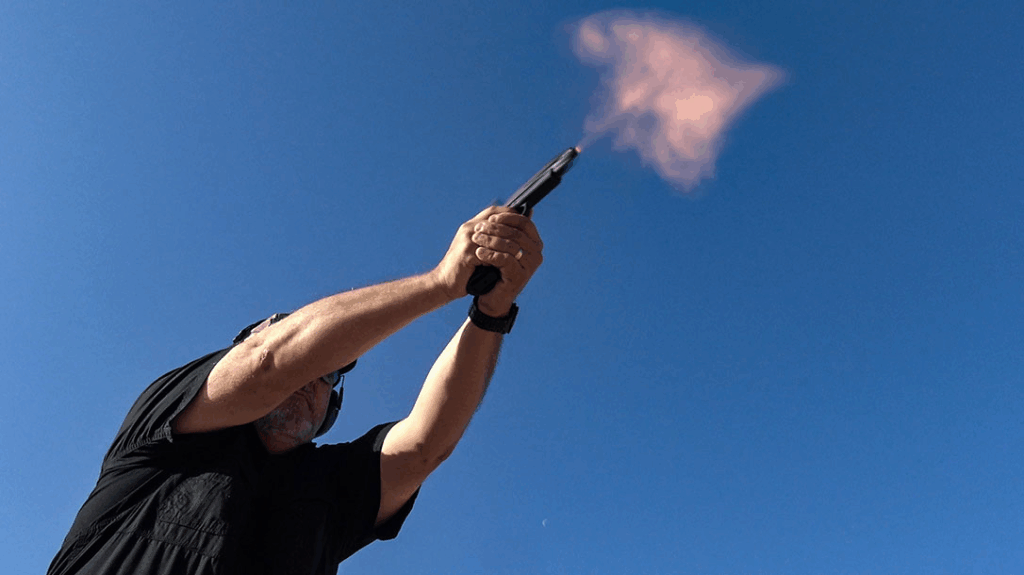

For most new shooters and even experienced ones, recoil anticipation is a silent saboteur.

It’s the reason those tight little groups end up pulling low-left for right-handed shooters. It’s the reason a shooter can see their sights perfectly, have the fundamentals seemingly locked in, and still miss their mark. Recoil anticipation is a natural, physical reaction to a violent mechanical process. But it’s also a problem that can be solved.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

We’re not talking about flinching alone here. That sudden, reflexive movement after the gun goes off? That’s flinch, and it’s part of the conversation. But it’s not the whole thing either.

The deeper issue is what your body is doing before you pull the trigger to initiate that sequence of events.

It comes down to your brain sending the signal to shoot and your muscles trying to “help.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Anticipation Happens “Before”

Recoil anticipation isn’t about what you do after the shot. It’s about what is happening beforehand. Once your brain decides to shoot, there’s still a sequence that needs to unfold: pressing the trigger, managing the trigger wall, engaging the sear, igniting the primer. That all takes time. During that time gap, your body often starts “prepping” for recoil. This may cause you to tighten your grip, dip the muzzle or unconsciously push the gun downward in expectation [of the blast].

These pre-shot cues result in a misalignment of the sights just as the shot breaks. On a 3-inch target at 21 feet, even a few thousandths of movement can throw the impact off-center. This isn’t a random movement either. It’s your body trying to do the “right” thing at the wrong time.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Recoil flinch happens to just about everyone—even experienced shooters. If you load a snap-cap into a “good” shooter’s magazine without their knowledge, you’ll almost always see the gun dip or shift when the trigger breaks. That doesn’t mean they’ve failed. It’s not the “gotcha” moment people make it out to be. Experienced shooters already subconsciously expect recoil, so their body began returning the gun to zero. This is part of managing the handgun during the shooting process.

If the movement is dramatic or excessive, it could signal a deeper issue. (But not always). The key is understanding when the movement occurs. If it happens before the hammer falls, that’s recoil anticipation. If it happens after, it’s just recovery. That difference matters.

The Gun & the Problem

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

This is worth repeating: modern handguns, especially defensive pistols, are capable of decent mechanical accuracy. If you mounted most polymer-framed pistols in a bench rest at 7 yards, you’d see single ragged-hole performance with quality ammunition. If your hits are drifting, it’s not the gun, it’s you.

It’s always tempting to speed up and make-up for mistakes that way. Inexperienced shooters think they can shoot through the problem. But you can’t miss fast enough. Accuracy first, then speed. That’s the only path that works in the long term.

Flinch Fits

Handgun flinch is easier to spot than anticipation. It’s dramatic. The shooter blinks, drops the muzzle, or jerks the trigger. But even here, there’s nuance. Instructors often use snap caps to test students, placing an inert round randomly in a magazine. When the trigger drops on the dummy round, the shooter’s reaction is telling.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

But here’s the key: it’s not just about whether the shooter flinches, it’s whether the gun moves before the hammer falls. That’s the diagnosis. The gun should be steady at the moment of ignition. Flinch is a consequence of anticipation. If you’re flinching, you’re probably anticipating.

Training for Control

One of the simplest short-term solutions is to grip the gun tighter. It may feel like a brute-force fix, but it can immediately stabilize the muzzle and mask anticipation behaviors. Grip the gun tight, until you’re almost shaking. A stronger grip also gives the shooter better feedback during recoil and recovery.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Snap cap drills remain one of the best tools for diagnosing and fixing anticipation. Load one or two inert rounds into a magazine at random. Or better yet, have someone else load them behind your back. When you hit them during a string of fire, watch the muzzle. Was there movement before the trigger dropped? If so, you’re anticipating the shot. These drills also prepare you to recognize and clear malfunctions, building better mechanical confidence.

Filming your practice session can provide unexpected insights. Use slow-motion video if possible. A smartphone on a tripod aimed downrange can show minute movements you weren’t even aware of. Video doesn’t lie, and it rarely flatters. That’s a good thing. Recording yourself can also help unmask things such as re-holstering without looking at your holster and garment.

Probably Shooting Too Fast

Many students are simply rushing their shots. They want speed and precision at the same time without building the process underneath it. A good shot needs a checklist: stance, grip, sight picture, trigger press, follow-through. If you skip steps, your bullet holes will let you know.

I notice this especially among students who start carrying a firearm after becoming a parent or assuming a new responsibility. That urgency to be capable, to be ready, sometimes pushes people to seek performance before they’ve built their foundational processes. In a defensive context, it’s not just about getting a shot off, it’s about getting a good shot off, under pressure–when it counts.

The goal is to develop a process for producing an accurate shot quickly. That process must live in the body. The hands, the arms, the eyes, the core, they have to be on autopilot so your brain can think about the problem in front of you. Developing automaticity, that’s what it means to train.

Trust the Trigger

The trigger press remains the most intimate part of the shooting sequence. It’s also the easiest place to inject error. A good press is steady, deliberate, and surprise-breaking. Yes, with time and skill, you’ll be able to shoot faster with deliberate control, but early on, each shot should be a surprise. Your sight picture needs to stay sharp, and you need to keep applying pressure so that the trigger breaks without warning.

That’s how you build confidence with your gun. It also helps with managing fear of recoil. When you see consistent hits, and you realize the gun isn’t hurting you—you begin to trust your skills and the device in your hands.

Final Flinch

Don’t forget your breath. Holding your breath increases tension, reduces oxygen to the muscles, and adds to the body’s natural stress response. Stay relaxed. Breathe between shots. Let your body move fluidly but with purpose.

Bring the gun to your eyes, not your head to the gun. That small postural change reinforces repeatability. Your eyes shouldn’t hunt for the sights. They should appear where your focus already is.

The Way Forward

Recoil anticipation and flinch aren’t permanent problems. They’re learned behaviors and they can be unlearned. But to do so, you need to be honest with yourself. You should also document your performance and follow a process. This will help you stay accountable. Grip tighter. Shoot slower. Diagnose movement. Film yourself. Use snap caps. Learn to trust the process more than the outcome.

Once you can make one accurate shot on demand, speed is just a matter of rep counts. The goal isn’t just to shoot better, it’s to shoot well on purpose, every time.

WHY OUR ARTICLES/REVIEWS DO NOT HAVE AFFILIATE LINKS

Affiliate links create a financial incentive for writers to promote certain products, which can lead to biased recommendations. This blurs the line between genuine advice and marketing, reducing trust in the content.

The post Mastering Recoil Anticipation (And Flinch) appeared first on Athlon Outdoors Exclusive Firearm Updates, Reviews & News.